SNC Study Will Help Raise Visibility of Oneida Nation

The considerable economic footprint of the Oneida Nation in northeast Wisconsin is still little known in the region. With the help of findings from a St. Norbert faculty-student team, the tribe’s leadership is set to change all that.

“People hear Oneida Nation and the first thing they think of is there is gaming,” says Marc Schaffer (Economics), director of the CBEA. “That is far from true in terms of the number of entities, economic enterprises, the number of social services they have. They are a massive organization, but most people don’t know about it.”

Intent on countering the general public’s misconception, Nathan King, director of legislative affairs for the tribe, sought assistance from the St. Norbert College Center for Business & Economic Analysis (CBEA).

In late August of last year, Schaffer, CBEA research analyst Alexa Brill ’18 and Sandra Odorzynski (Economics) began an eight-month economic study of the Oneida Nation’s economic impact on the two-county region of Brown and Outagamie.

“We worked with their statistician, who collected a bunch of data from their entities,” says Schaffer. “We used our input/output analysis process to come up with our numbers.

“Taking all the stuff they gave us, we broke it down into nine categories,” he adds. “The biggest category is their economic enterprises, which includes gaming, recreation, Thornberry Creek Golf Course, hotels, convenience stores, retail shops, tobacco shops. They have a construction company, an engineering company. All of that is under the enterprise umbrella.”

The study examined first or direct effects, followed by indirect and induced effects. For example, Thornberry Creek at Oneida Golf Course generates $3 million in annual revenue. The business employs 183 people and pays out approximately $1.2 million in compensation. Once that money is spent, two other effects hit the economy.

“Because the golf course is here, other businesses are in business because they are getting expenditures from the golf course. That’s the indirect effect,” explains Schaffer. “The third effect is the induced effect. Because these other companies employ people, because the golf course is paying them for services, all these people have income and they then spend the income in the local economy.”

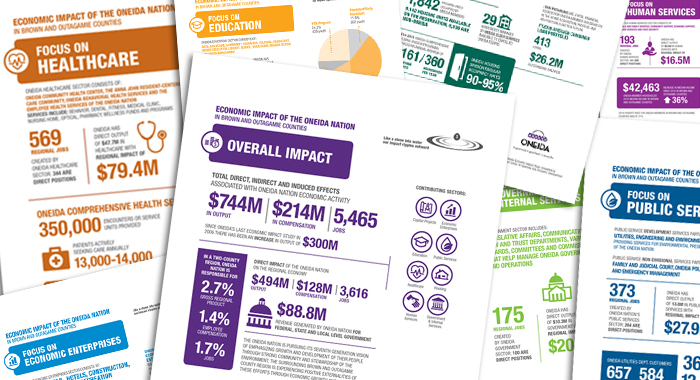

In addition to enterprises, the CBEA study explored the economic impact of the Oneida Nation on health care, public services, government and internal services, human services, housing, and education.

“The Oneida Nation provides services to its membership that offset what the local government may provide,” says Schaffer. “If you look at their school, those are 450 students not in the local school system, not covered by local property taxes to educate those students [a savings of nearly $6 million for local school districts]. Youth enrichment services [for the Oneida Nation] averages $10.5 million a year paid in scholarships, of which $2.8 million stays in higher education in Brown and Outagamie counties.”

The CBEA team analyzed 233 line items for the Oneida Nation study. “To give you a scope of what that means for what we do, we did one of the CP Center, we did one for the Farmory; each one of those would be like one of the 233 things we did for this one,” says Schaffer.

A 27-page summary was released at the completion. The study concluded that the total direct, indirect and induced effects associated with the economic activity of the Oneida Nation are $744 million in output, $214 million in compensation and 5,465 jobs.

The study can help clear up some misconceptions, including that the nation only undertakes gaming enterprises, and that the tribe doesn’t pay taxes, which is far from true, says Schaffer.

“They only get 19 percent from federal and state money,” he explains. “Eighty-one percent of the funds they use are their own funds. The study gives them third-party validation of what they are doing; some numbers they can cite and note.”

The Oneida Nation made a donation to the CBEA for the study.

“We started the center four years ago. I try to pair students up with small businesses and nonprofits,” explains Schaffer. “We’ve done projects across the board. Many were pro bono. We are now getting big enough that we are into the non-pro bono work. If we can add some value from St. Norbert to our local community, what’s a better way to do it than to take some of our students and let them apply the things we are teaching them with a side benefit of serving the community? It’s win-win across the board.”