The Stars Align for Student Researcher

It all began in 1900 as a marketing ploy. Ándre and Édouard Michelin, owners of a French tire company, wanted their countrymen to purchase more cars – because the more cars that were sold, the more need for Michelin tires. So they created a free guidebook for motorists with maps and information on where to buy gas, sleep and dine – the Michelin Guide.

That small, red book evolved over time to be an arbiter of some of the best fine-dining establishments in the world, with chefs vying to snag an award of one, two or three stars, rankings the guidebook dishes out annually. Today the guide rates more than 40,000 establishments around the globe using anonymous food critics, dubbed inspectors.

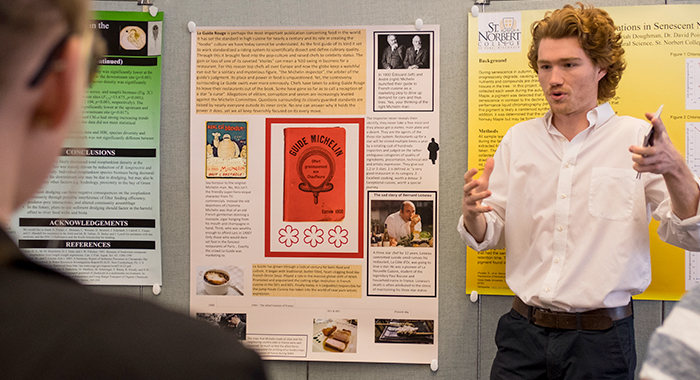

“This choice of how to market cars in 1900 evolved into the way we judge food today,” says Frank Cushman ’18, who created a presentation on the topic for St. Norbert’s Undergraduate Research Forum last spring. He was assisted by Tom Conner (French).

“We always do a little culture in our language classes, so I talk about food and introduce the Michelin Guide,” Conner says. “The French take food very seriously.”

Cushman researched the guide's history via online resources, which included watching videos and listening to podcasts. He also studied old guides Conner had in his collection.

It’s very difficult for a fine-dining establishment to snag a one-star rating in the Michelin Guide, Cushman says, let alone two or three stars. And earning a star or two in a given year is no guarantee you will receive the same ranking in the future. Sometimes the pressure to attain or keep a star is too much – a fact that has caused some controversy and criticism during the last 10 to 15 years.

In 2003, French chef Bernard Loiseau committed suicide, ostensibly because newspaper reports hinted his restaurant was about to lose its three-star status. Industry insiders also began leveling charges of a Euro-centric rating system that favored eateries serving food from particular countries, such as France and Italy. An apparent bias toward male chefs was also noted, all of which led many to ponder if the Michelin Guide’s power and influence was misplaced.

These controversies intrigued Cushman. “We’ve come to this crossroads,” he says. “What does it mean to have good food? How does it disenfranchise people if a major food-ranking institution favors food made by men, and in a certain style?”

Michelin is starting to navigate such issues, he says, noting a major positive of the guidebook is that over the decades it pushed chefs to take food and its presentation to new levels.

“I thought this was a fun little topic,” Cushman says, “but I came out of the project with a lot of really deep questions.”

Sept. 4, 2018